Did I find the inspiration for Beethoven's Opus 109?

While practising the Variations of Piano Sonate Opus 109 in E. The theme resonated deep in my soul and it kept reminding me of a Choir composition I had just the month before played with several Choirs. Could it be? So I started searching but found nothing. Making enquiries at a good friend of mine, Alberto Portugheis, Vice President of the Beethoven Society of Europe, gave as a result that it was not known where the Air of the variations came from and Beethoven had composed it himself. The first movement of the Sonata was added to it at a later date.

But I soon started recognising many quotations from a composition of Silesian origin and a German kapelmeister had added some orchestral accompaniment. Joseph Schnabel lived from 1767-1831 and was a contemporary musician with Beethoven. Transeamus usque Bethlehem is performed played around Christmas and it is very well possible that Beethoven had heard it and was inspired by it.

Only the theme to go by was a bit meagre, hence I started looking for more quotations and the emotions connected to them. I was not disappointed.

But let us start with the theme, which prompted my quest.

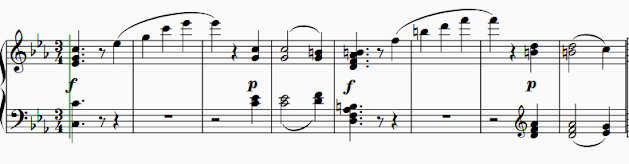

Beethoven's theme of the Air reads:

Beethoven gives the initial theme three times, the second time moving to the upper-dominant. The Transeamus theme is the same, moving to the dominant and then descending to the 7th of this dominant. Also Beethoven did this. Then there is a descent in thirds, but Beethoven moves to the dominant and Transeamus returns to the Tonic, hence the descent in thirds is a bit longer there..

Hmm... For me this seems very obvious. But I could not imagine that nobody has ever noticed. Or perhaps the Beethoven police was hard at work? Beethoven was a son of the Enlightenment and would not as would Bach be influenced by a Church composition. Wouldn't he?

I needed more.

Initially, probably, the Air was ment to be a second movement, with the Prestissimo being the first. So no wonder we find a reference to the theme in the middle of Transeamus. I would have to look at the Prestissimo movement to look for some more clues. I now was looking for the possibility of Opus 109 being influenced by Transeamus. Because if that was a plausible possibility, then it would automatically result in the conclusion that the Air of Opus 109 was inspired by Transeamus.

I did not expect to find anything remotely useful, but to the contrary I was overwhelmed by what I found.

Transeamus offers a boisterous statement of ascending notes of the Tonic chord of G major, whereas Beethoven does this the key of E minor.

Then Transeamus descends to the sub-dominant and closes in the Tonic. Beethoven keeps ascending, but also by switching to the subdominant and ending in the Tonic chord. Both final cadenz sequences are very similar.

With Beethoven, this opening is a single statement in fortissimo. He proceeds after this with a lyrical piano response to this statement. Also Transeamus is a statement. A statement about going somewhere.

But also consider this:

A small adaptation of the Transeamus theme uncovers more similarity.

Ok. For a start that is not disappointing. Is there more?

In the response Beethoven reworks what the reason is for his bold opening. Is he going somewhere? In Transeamus the cause is given too. usque Bethlehem. The material found also in de accompaniment of Transeamus is a striking similarity.

Let us look what the excitement in Transeamus is about:

In Transeamus they are going so see how the Logos became a human born baby. But Beethoven is equally excited about the purpose of his Statement.

Not convinced yet? Let's see how these expressions of excitement end in both.

Beethoven extends the repeated notes over a multitude of bars, he does so much more with whatever material. But both end in the same way. Transemus in a return to the Tonic of G major, but Beethoven to the dominant Key of B and then he repeats it in bar 76-79 in Tonic key of E minor. But Beethoven reworks it in marvelous extended counterpoint.

It looks like all the material used in the Prestissimo has striking similarities with the material found in Transeamus. The material in the middle of Transeamus 'Mariam et Joseph et infantum positum in preasipio' is found in the Air used for the variations.

Leaves still one bit of material in the Transeamus unused. The 'Gloria'!

Beethoven alludes to it in the final variation. Number VI. But he extends it there in a never ending set of trills in left and right hand as final homage to his creator. What does this all mean? That in Beethoven the ultimate enlightenment en human achievement Transcends into a homage to the born logos?

For me it seems obvious that Beethoven was influenced by Transeamus, and he had already written two movements for it the Prestissimo as first movement and the Air as second movement. Later he decided to use another movement as movement, go overboard with the 'obligatory' second movement as air, boldly putting the Prestissimo there. Hence the Air became the final movement of a new Sonata. Perhaps he added the second variation to make a reference to the newly added first movement. And ended with the spectacularly spiritual last variation.

Art Zegelaar (c) 2023 The Music Experience. All rights reserved.